Fellows of the prestigious Fulbright program faced big problems after the program’s sponsors (Institute of International Education and Cultural Vistas) were recognized as undesirable organizations in Russia in March 2024. T-invariant reported on this in detail last summer. What is happening today with young scientists from Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine?

These problems were recently discussed at the roundtable “Students from Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia in the United States under conditions of war and dictatorship: challenges and solutions.” One of the organizers of the conference, American Human Rights Russian Speaking Association is a well-known organization in the U.S. and the former Soviet Union that helps immigrants from the former Soviet Union to overcome obstacles to their integration into American society, to promote their self-organization and participation in public life. Their partner, Liberty Forward, is a young organization. It was designed to help participants of Fulbright programs: students and young scientists, fellows of Institute of International Education and Cultural Vistas programs in the U.S. when the programs sponsoring them were deemed undesirable in Russia. Fulbright and YEAR participants who found themselves in America at that time united to fight for the future, for their rights and the opportunity to continue their careers in the United States.

Return to Ukraine

Lubov Palchak, a Ukrainian citizen, MD from the University of North Carolina, spoke about the problems she encountered while trying to obtain a non-immigrant visa.

“I lived most of my conscious life in Bakhmut,” Lyubov says. – In 2014, when hostilities began on the border of Russia and Ukraine, I studied in Kharkiv. But I visited my parents in Bakhmut on a regular basis. On one of these visits, in the spring of 2014, a military unit near our house was attacked with grenade launchers. The sensations were unpleasant. In general, the war in the region was felt long before 2022. The entire railroad connection was disrupted, Bakhmut and various cities around it were under the occupation of the DNR, and it was impossible to get there.

Nevertheless, after graduating from Kharkiv University, she was assigned to a communal pharmacy in Donetsk. But Palchak decided not to work on the assignment, but to go to Kiev. There she successfully completed her internship.

“By this time there was a feeling that the situation was normalizing,” Lyubov says. – The Ukrainian authorities had stabilized, business started to return. I had a child. And in 2016 we returned to Bakhmut: there was real estate, comfortable and safe conditions for the whole family.

In 2017, Lubov found a job at the Donetsk Medical University, part of which was located in the buildings of Slavyansk, Kramatorsk and Druzhkivka. It was in Kramatorsk, where the young family eventually moved, that Lyubov met February 24, 2022. With her young son, she left for Poland, where she immediately began looking for an opportunity to continue her graduate studies and her scientific work. Palczak contacted Alexander Kabanov, a professor at the University of North Carolina. And his colleague from Germany offered an internship in his lab while the long process of applying for visas to America was underway.

“The scientific group accepted me perfectly,” Lyubov recalls. – As a Ukrainian refugee, I could stay there for up to five years, get a residence permit and stay. But Eshelman School of Pharmacy better suited my scientific interests, the prospect of applying my knowledge there was higher. And Professor Kabanov and I went ahead with the exchange visa.”

It was a non-immigrant visa for moving to the U.S.: it was assumed that Lyubov would return to Ukraine after the internship. But at the interview at the American Consulate in Munich Lubov was refused: she had a small child with her; it is not known whether her house is intact; there are no guarantees that she will return.

Today, Lubov knows for sure that her home is gone. She was able to get to the U.S. and get an opportunity to work at Eshelman School of Pharmacy thanks to the United for Ukraine project. Today this program is frozen and it is not clear what will happen to the students who came to the United States under this program.

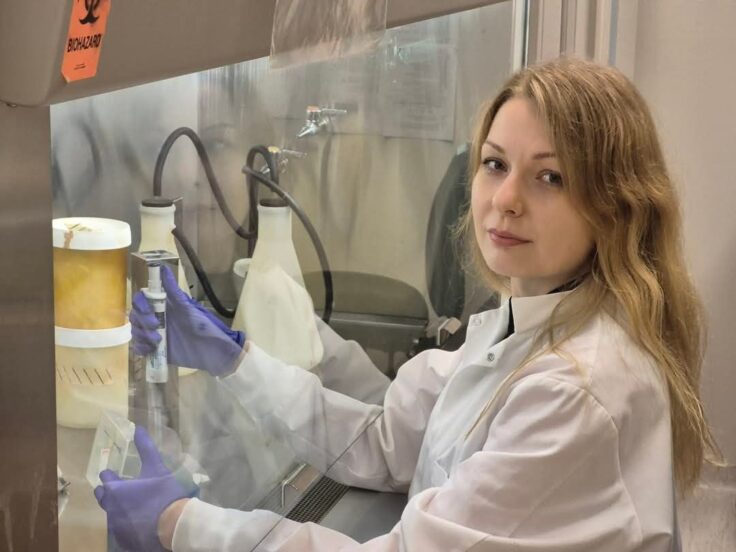

Palczak’s research topic is the development of delivery systems for drugs. The research group where Lubov is interning is working on drugs that improve therapy for triple-negative breast cancer. In the near future, the group hopes to receive a patent for an invention to which Lyubov has made a significant contribution. The work demands a lot of her time and energy. But collecting documents for an immigrant visa is a separate, and considerable, time. Lyubov admits that now she is facing an acute choice: to spend time on further work or on collecting documents to be able to work.

“My doctoral studies will be completed by the fall of 2027. The status that allows me to stay in the U.S. expires in the fall of 2026. It is impossible to extend it under the United for Ukraine program: the program was frozen by the administration of the current president,” Lubov sums up. – What will happen if I return to Ukraine? The war continues, medical and pharmacological research is impossible. Most likely I will have to serve in the army.

A separate problem is that the city where Lubov lived is now under Russian control, and Palchak is not ready to become a Russian citizen for ideological reasons.

Lubov’s academic advisor, Alexander Kabanov, notes that her story cannot be called unique: “First, there has been dramatic instability and a change in U.S. policy recently, though it was not a big surprise, establishing a relationship with a regime that is fighting the people of Ukraine. We can see from Trump’s previous term that he and his administration are impulsive and irresponsible. I’m afraid they may yet crack down on the unprotected classes in the US, including Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians. Lyubov has already said that United for Ukraine program projects have been frozen, but the issuance of temporary refugee protection has also been frozen. In addition, the Trump administration can announce at any moment that everyone who has this status or is waiting for it should return home.”

According to Kabanov, Lubov’s situation is not yet the worst. Many Ukrainians in the U.S. have permits expiring already this year, and what they should do next is unclear. At the same time, according to Alexander Kabanov, there are not so many Ukrainians in the United States – about 200 thousand.

“Many would like to stay in the country, to work quietly, to be useful to the U.S. economy, – draws attention to Kabanov. – Let’s take Lubov as an example. She is a wonderful student, an excellent specialist. Recently, in our field, cancer treatment, Palchak has made an important discovery, and we have applied for a patent. Such people do not just work themselves, they help other people and invent things that can create new jobs.

Kabanov admits that he is disappointed not only with the Trump administration, but also with the Biden administration: “When the exodus of scientists from Ukraine and Russia began, Biden urged us to accept all the brains we could. But it was unrealistic. Getting a visa to the United States is very difficult for both Russian and Ukrainian scientists. Good specialists, whether they are Ukrainians, Russians, Belarusians or anyone else, are a great asset to the economy. But we are losing them. Biden has done nothing to retain such specialists, and Trump is doing nothing. I never tire of telling our congressmen that.”

Go back to Russia

Tatiana Gabriichuk, a master’s student in public administration (MPA) at Indiana University Bloomington came to the U.S. in 2023 and became the last Russian Fulbright Scholar at the university. She has only one semester left of her Master’s degree in Public and Environmental Affairs, where Tatiana specializes in the sustainability of local public services (e.g., 911 services, fire departments) and the restoration of war-torn cities.

As Gabriichuk notes, she has faced pressure from the Russian authorities her entire academic career. While defending her diploma at St. Petersburg State University, her supervisor was fired on the day of the defense for her political views. Her first international Master’s program “Human Rights and Democratic Governance” with a specialization in Human Rights and Democratic Governance at the National Research University Higher School of Economics was closed in April 2022 for political reasons. The second international master’s program “Energy Policy in Eurasia” (ENERPO) at the European University in St. Petersburg, according to Garbijchuk, also ceased to exist as an educational program.

Tatyana cooperated with five different organizations recognized as undesirable in Russia. Moreover, participation in the activities of such an organization can lead to imprisonment of up to four years. The Fulbright program that brought Tatyana to the United States was declared “undesirable” in Russia in 2023. Receiving money from it (including scholarships) and participating in its activities is a criminal offense under Russian law.

“The Fulbright program was supposed to be a bridge for us, an opportunity to build mutual understanding between peoples,” Gabriichuk says. – But for Russian Fulbrighters, that bridge has been burned: our participation in the program is considered a criminal offense in Russia. Our legal status in the U.S. became precarious, and we were caught between two systems that don’t take cases like ours into account.”

Tatyana left Russia on February 24, 2022, just after the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, and joined the anti-war organization Russians Against War Antalya (recognized as undesirable in Russia), where she helped Ukrainian refugees. In Turkey, however, she met her husband, a Belarusian citizen, who is now in the U.S. with her on a J-2 visa.

“My husband’s situation is even more complicated,” she says. – In Belarus, he was facing jail time because of political persecution. As a result, he is in the U.S. on a Russian Fulbright visa as a family member. This adds another layer of complexity to our already complicated case. According to Tatiana, getting political asylum in the U.S. was unexpectedly difficult because Tatiana’s husband had briefly lived in Poland and Turkey. The U.S. authorities believe that he could return to live in one of these countries. But this would require decent savings, and the couple does not have any.

Now, on the advice of a Fulbright consultant, Tatiana plans to complete postgraduate academic training that will allow her and her husband to remain in the United States until August 2026. During that time, Tatiana hopes to get an exemption from the two-year rule (under the J1 visa rules and the treaty, all exchange program participants must return to their home countries for at least two years after completing their studies) and switch to another immigrant visa. But as she began to move forward with this seemingly successful plan, Tatiana encountered a number of unpleasant surprises.

“For example, I was accepted into a joint U.S.-German project, and I was supposed to travel to Germany as part of that project,” she says. – But the Fulbright advisor strongly advised me not to leave the U.S. until I finished my studies. I might not be allowed to come back. So I had to refuse.

Another of Tatiana’s pains is not being able to see her family for years to come. She and her husband face criminal charges, and it is virtually impossible and very expensive for Russian citizens to get a visa to the United States.

“They want to silence us.”

Violetta Soboleva, director of Liberty Forward and a graduate student in the educational psychology program at the City University of New York, says that Tatyana Gabriichuk is far from the only Fulbright Scholar who has found herself in a similar situation.

We asked our consultants from Institute of International Education and people associated with Fulbright what could be done in such a situation,” says Soboleva. – Most of them advised not to stay in the US and not to return to Russia. But we have signed documents with the obligation to return to Russia after the exchange program. Moving to any other country does not cancel the two-year rule, which means that it is still impossible to stay in the U.S. legally without two years of residence in Russia. And most of us didn’t have the money to move and get visas, either.

Violetta Soboleva says that the Fulbright program management does not meet the needs of the fellows: “They are rather trying to get rid of us, they want to silence us. The only thing they did was to remove the list of fellows from the program’s web page. They feel that in this way they have taken care of our safety. One of the fellows of the program tried to get support from Joel Erickson, the former director of the Fulbright program in Russia, but was told that we knew what we were getting into when we signed the document committing to the two-year rule, and Fulbright owes us nothing.

Another member of Liberty Forward, Denis Vavaev, agrees: “I often hear from Russian-speaking people on both sides of the border that we are not threatened. But we are not Yashin or Kara-Murza and nobody needs us. I should recall that this story began with a statement by Naryshkin, director of the Foreign Intelligence Service, naming seven different programs, including Fulbright, that are training a “fifth column.” In addition to Fulbright, Cultural Vistas, which has never even had an office in Russia, was added to the list of undesirable programs. But they give their grants for postgraduate internships in large numbers to Fulbright graduates from all over the world. In other words, Fulbright students who received grants for postgraduate internships automatically cooperated with two undesirable organizations, which could lead to criminal charges.

In addition, Vavaev pointed out that Fulbrighters for the U.S. are not just random people, participants in some programs. They are students and young scientists whom the U.S. has carefully selected, including for their cultural values. “We would like to do good in our home country, but it is really dangerous to return to Russia,” says Denis. – Besides, we observe how the scientific community in Russia is actively isolated. The same processes are observed in Belarus. And as for Ukraine… The timing of the end of the war is absolutely unpredictable, and it is unclear when it will be possible to do science there normally and effectively. That is why we ask for an opportunity to stay here and do good”.

The citizens of Belarus, who have J-1 visa, have been waiting for the abolition of the two-year rule for at least a year and a half – each of their cases is considered as cases of individual political persecution, because the Fulbright program is not prohibited in Belarus. The ban on changing passports outside Belarus complicates the situation. An expired passport does not allow to get a Real ID (identification card) in the United States. This means that there is no possibility to move freely even within the territory of the United States (from May 2025, it will be impossible to buy an airplane ticket without a Real ID or a valid passport). Moreover, without Real ID it is forbidden even to enter government buildings.

A Fulbright student from Myanmar, Mon Soe, found himself in a similar situation. “I am not from Ukraine, Belarus or Russia, but I am going through similar problems,” he shares. – If I return to my home country, I will immediately be drafted into the army and forced to fight against my own people: we have a civil war going on. About 400 students will be forced to return to Myanmar after USAID funding is frozen. What we would like to do is not to fight, but to do science!”

The discussion of the speeches of Fulbright Fellows at the round table was heated. Most speakers doubted that the current government could adequately respond to the problem of Fulbrighters now in the United States. Gordon J. Humphrey, a former federal senator in New Hampshire from 1979 to 1990, commenting on the difficult situation facing students in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, said: “The U.S. state is making a terrible mistake, both from a humanitarian point of view and from a strategic point of view. People like you are our allies and friends. I think we should let you stay in our country. Besides, there are a lot of Russian-speaking people living in the US, and that’s thousands of electoral votes. Trump needs to understand why this is important for the US economy and strategically important for the rest of the world. Let’s leave aside the humanitarian issue, even though it should be paramount. But it is pragmatically advantageous for the US.”

Marcy Shore, a history professor at Yale University, admitted that she has a pessimistic view of what is happening in the US today. She doubts that Donald Trump and Ilon Musk will lead the country to prosperity.

In her opinion, they, like Vladimir Putin, do not act in the interests of their people: “Putin burns the resources of his country, its population, completely exterminates cities, and then on the ashes declares his victory. He and Trump are very similar. They are very unstable regimes. I realize I sound like Cassandra, but I have no optimistic words for you. I’m afraid that Ukrainians today should not trust us, should not count on us. This is not to say that there are no “good guys” in the US government. But their voices are getting quieter and quieter. I’m afraid that people who are amoral and psychopathic have come to power.”

According to a former U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services employee who wished to remain anonymous, USCIS processes more than 10 million different requests a year, and it’s all a kind of zero-sum game: there is much more work than the people who do it. Therefore, in his opinion, situations of long consideration, inarticulate answers, and delays may be related not to political decisions of the leadership, but to a banal shortage of people. The queue for the “return home waiver,” including the waiver of the two-year rule, according to which Fulbright program participants must return to their home country and work there for two years, is too long. We can look for reasons to move some specific applicants to the front of the queue, but we must realize that this will lengthen the waiting time for others, for whom a decision as soon as possible is also important.

During the discussion there were several ideas on how to move forward in solving such bureaucratic issues. In particular, they discussed the possibility of talking to Ilon Musk, who, according to some of those present, should be interested in solving such problems. There was also a suggestion to appear in the media as often as possible, to attract public attention. Tatiana Yankelevich, an independent researcher affiliated with the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University, urged U.S. citizens to contact their senators: “I think we should remind them of the promises Trump made before his inauguration. For example, on the first day of his presidency, he promised to unconditionally lower the price of eggs and other foodstuffs; to stop the war in Ukraine; to stop the conflict in Gaza; and to return all hostages. To date, egg prices continue to rise, the war in Ukraine continues to rage, the conflict in Gaza has not been resolved, and hostages remain in the hands of terrorists. The least we could do is have our representatives in the U.S. Congress remind the administration of these promises, post it on their websites.”

Leave or seek political asylum?

After the roundtable, Liberty Forward representatives Daria Nefedova and Denis Vavaev shared some happy news.

“We have contact with the state department. We managed to set up a track to remove the two-year rule,” shares Denis Vavaev. – As a result, the processing time for Fulbrighters has been reduced to 5-6 months instead of 18 months like everyone else. Apparently, the State Department and USCIS have reached an internal agreement that there are risks for Fulbrighters in Russia, but our cases are actually managed manually. However, this system applies only to the Fulbright program. And the cases of YEAR program participants are still considered in the usual mode”.

Liberty Forward hopes that the work of the Trump administration will not negatively affect them. To date, since the beginning of Trump’s presidency, eight Fulbrighters have successfully cleared the two-year rule exemption.

“The other issue is that removing the two-year rule doesn’t completely solve our problem,” Denis says. – Yes, we don’t have to go to our home country anymore, but we don’t have the status that will allow us to stay in the US. We can apply for a work visa, but it may take two years to get it. And there is no legal basis to stay in the U.S. during that time. We have to either leave or apply for asylum. And getting political asylum is an even longer process. For scientists, this way is also bad because they can’t leave the country during the entire waiting period, which means no trips to other laboratories, no international conferences and seminars.

So far Liberty Forward works only with Russians, but at the same time Belarusians and even some Ukrainians turn to them to solve their problems. The problems of Russians and Belarusians are similar in many respects, it’s just that in Belarus they do not persecute Fulbrighters in general, but rather individually for political reasons,” Denis explains. – But there are very few Belarusians, who came to the U.S. under the Fulbright program, 1-2 people a year. The situation with Ukrainian students is different. Their problem is not bureaucratic, but rather political.

Denis admits that their young organization understands that it is necessary to help Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians who are already studying in America and those who would like to study here. But Denis and his colleagues are sure that the organization should, in addition, train Russian specialists who can return home when the situation changes: “We will need specialists in a conditional transition period. After all, it will come at some point. And people who will be able to build democratic institutions should be prepared in advance. There were no such people in Russia in the 1990s. As a result, the economic system was built, but democratic institutions were not created. It is necessary to prepare in advance people who will carry out the same lustration. I think we all realize this, having learned from bitter experience.

The situation with international students in the United States is not getting any easier. But one should realize that young scientists and students who will lose the opportunity to study and work in the U.S. face not just the question of choosing another country to live in, but also the question of personal security. America, by kicking these scientists out of the country, undoubtedly loses young educated loyal residents, but what will the U.S. and science as a whole gain if these young people are forced to return to Russia and go to prison or are drafted into the army? This is a question with an unambiguous answer.