In June 2023, T-invariant published an interview with Mikhail Sokolov, a sociologist of education and science and a professor at the European University in St. Petersburg. Among other topics, the scholar suggested that the war would have little impact on the state of social sciences in Russia. Has his opinion changed two years later? What is happening to the social sciences today, and what lies ahead for them? These questions are now being discussed with Mikhail Sokolov by Sergei Erofeev, a sociologist at Rutgers University (USA) and president of RASA, the global association of Russian-speaking scholars.

Mikhail Sokolov

Born in 1977. In 1999, he graduated with honors from the Faculty of Sociology at St. Petersburg State University (SPbGU), specializing in social anthropology. In 2003, he completed his postgraduate studies at the Sociological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAN). He holds a Candidate of Sciences degree in sociology (dissertation: Self-Presentation of Organizations in the Russian Radical Nationalist Movement). Sokolov has worked at the Center for Independent Sociological Research, St. Petersburg State University, and the St. Petersburg branch of the Higher School of Economics (HSE). From 2006 to 2023, he served as an associate professor and later a full professor at the Faculty of Political Science and Sociology at the European University in St. Petersburg. He is one of Russia’s leading sociologists in the fields of science and education.

Parallel Anti-Westernisms

Sergei Erofeev (T-invariant): Two years ago, an article by Theodore Gerber and Margarita Zavadskaya was published with the clickbait title “Rise and Fall: Social Sciences in Russia Before and After the War.“ Shortly afterward, your interview with T-invariant came out, in which you seemed to disagree with them, arguing that the war would have little impact on social sciences in Russia. Who turned out to be right in the end?

Mikhail Sokolov: In theory, everyone could be right because the thesis and antithesis operated on different planes. The thesis was that social sciences in Russia flourished due to academic freedom and the opportunities for collaboration with foreign colleagues. The part of the state driven by rational modernization impulses supported this development. However, alongside this rational side, the Russian state also had an imperial and irrational one, which eventually gained the upper hand—resulting in the war with Ukraine. With the war’s onset, the authorities began tightening the screws, growing suspicious of international collaborations and foreign publications. Now, deprived of vital contact with Western scholarship and under censorship, Russian scholars are doomed to decline into insignificance. That’s the rise and fall.

T-i: Which part of this turned out to be true?

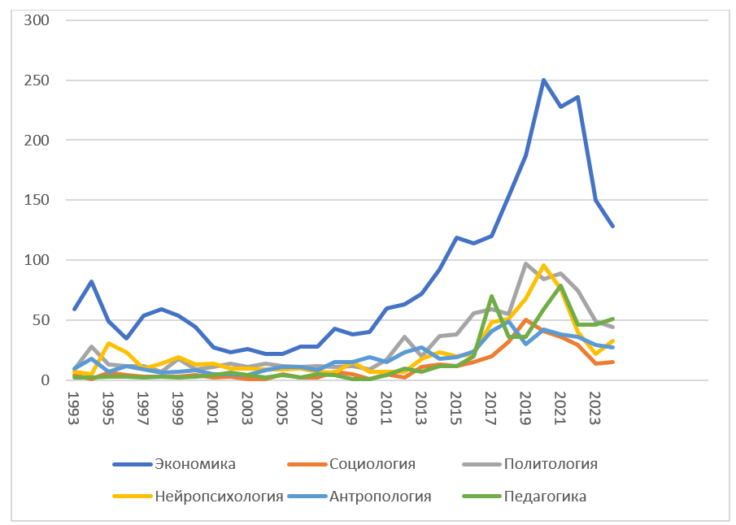

MS: That the rise and fall did indeed happen. This is easy to confirm by plotting a graph showing the change in the number of non-translated English-language articles in the Social Science Citation Index (part of Web of Science) where at least one author listed Russia as their country. Compared to the peak in 2021, 2024 shows a drop of over 60%. In absolute numbers, SSCI indexed 2,241 publications in 2021 but only 859 in 2024.

However, the reasons behind this decline remain debatable. In the early months of the war, there was much discussion about Western journals boycotting Russian authors. While isolated cases of this nature did occur, they largely remained exceptions rather than the rule. A more significant factor may have been the severing of international collaborations—which likely had a major impact on experimental natural sciences. But in the social sciences, collaborative work is far less common to begin with, let alone international collaborations.

A third potential factor could have been the supposed end of institutional pressure on Russian scholars to publish in Scopus-indexed journals. While this factor is theoretically significant, no such policy shift actually occurred at the time—despite the Ministry of Education and Science’s grand declaration of abandoning “hostile” citation indexes in the early weeks of the war. In reality, Scopus publications continued to be referenced in official documents until 2024. They were eventually replaced by the Ministry’s “White List“, which consists of roughly 95% of the same Scopus-indexed journals—minus those that fell out of favor (primarily Elsevier-owned titles due to the publisher’s pro-Ukraine stance)—plus a handful of journals from the Russian Science Citation Index, most of which were already in Scopus anyway.

Another possible contributor is the reduction in “guest” co-authorships. Universities worldwide, under publication pressure, had discovered that their metrics could be instantly boosted by hiring “legionnaires”—researchers who contributed little beyond attaching their names to papers with institutional affiliations. After the war began, the number of foreign scholars willing to associate with Russian institutions dwindled. However, this pool was never large to begin with; for Russian universities, the primary source of such co-authors had always been domestic institutes like the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAN). A more significant loss may have been researchers who lived dual academic lives, maintaining positions in both Russia and abroad but chose to stay abroad after 2022. While common in natural sciences, this phenomenon was rare in social sciences.

Finally, the most significant—and most obvious—factor for the social sciences and humanities has been outward migration. Dozens of studies have already attempted to measure its scale. A recent publication analyzed user mobility data from Meta (Facebook)—a platform Roskomnadzor has declared an “enemy of the people.” To be counted as a migrant, a user had to first log in regularly from one country for a year, then from another country for the following year.

It’s important to note that this is an extremely conservative estimate: not everyone uses social media, and some people moved between countries without staying anywhere for a full year, meaning they weren’t counted. Even so, this method yielded a figure of 860,000 people who left Russia in 2022 alone—higher than previous estimates.

T-i: How many of those who left during this recent, explosive wave of emigration were actually academics?

MS: Estimates vary. To get a clearer picture, I analyzed faculty turnover at the Higher School of Economics (HSE)—Russia’s primary employer of social scientists integrated into global academia during the pre-war decade. Specifically, I tracked recipients of HSE’s international publication bonuses in 2021 (718 researchers) and checked how many remained employed there by fall 2023.

The results were striking: only 75.3% still worked at HSE, meaning 24.7% had left. While some attrition is normal, HSE’s historical turnover was just 1–2% annually—unsurprising given its competitive salaries and younger-than-average faculty. This suggests an “excess attrition” of at least 20%, likely closer to 25%.

Given academia’s Pareto distribution (where a minority of researchers produce most publications), losing a quarter of internationally active scholars could plausibly explain the 60% drop in output. When high-productivity researchers exit, the ripple effects are disproportionate.

T-i: How did migration from HSE turn out to be linked to academic discipline?

MS: The proportion of biologists, neuropsychologists, and medical researchers who were nominated for bonuses but could no longer be found on the university’s website (over 50%) was significantly higher than that of political scientists and sociologists (under 30%). While biologists seemingly had fewer reasons to fear professional repression or restrictions, they left the country at a much higher rate.

It can be assumed that the decision to emigrate stems from a combination of factors, in which professional difficulties are of secondary importance. What takes precedence is a fundamental disagreement with the political course (and the fear that this dissent may come at a high cost if it draws the wrong kind of attention), as well as the unease of living under constant scrutiny—always wondering whether one has inadvertently attracted unwanted notice. On the other hand, the more “scientific” the field—that is, the greater the consensus within it about what constitutes meaningful academic achievement—the higher the likelihood of migration among its practitioners.

T-i: Because it’s significantly easier for them to find work abroad?

MS: Yes. This rational aspect of the decision to emigrate—that those who were confident they could continue their academic careers left more easily—may explain why precisely that quarter of bonus recipients who produced 60% of all publications disappeared from HSE’s website. And for these individuals, the chances of returning—whether due to failure to secure employment abroad or a sudden shift in political winds—are far lower.

Another factor is age. If you’re under 35, you can enroll in a PhD program and restart your academic life, treating everything as an exciting adventure. If you’re over 50, salary expectations are much higher (you’re relocating with a family, and the prospect of renting a room no longer seems appealing), job openings are scarcer, and the bar for academic achievements is correspondingly higher. That’s why younger disciplines, which had been rapidly developing in recent years, were hit harder. And that’s why the consequences of this academic exodus will be felt for decades to come.

T-i: Can we say that some factors driving academic migration offset others?

MS: I haven’t analyzed the natural sciences specifically, but yes—that could well be the case. At first glance, the trends in the presence of Russian authors in international publication streams appear fairly similar across both natural and social sciences.

Comparing English-language publication data by discipline is actually more complicated than it seems. For instance, the representation of Russian English-language and translated journals varies drastically across fields. In social sciences, there are very few, and they’re quite marginal (in fact, Web of Science indexes just two—“Russian Politics and Law“ and “Russian Education and Society“—which I simply excluded). In physics, however, there are more, and they enjoy a far better reputation.

Alternatively, we could examine the presence of Russian authors in international mega-journals—for example, the various “Physical Review“ series, which publishes thousands of papers annually, has never announced a boycott of Russian authors, and remains traditionally popular among Russian scientists. Here, we observe a similar trajectory: from roughly 1,000 articles around 2010, peaking at 1,340 in 2019, followed by a sharp drop to 770 in 2024 (57% of peak levels).

To summarize this chapter in Russian science’s history, future historians will likely write something like: “As a result of the Russian leadership’s efforts to secure the country’s ‘proper place in the world,’ Russian science has shrunk by roughly half in the eyes of that world.”

T-i: Fine, the decline is evident. So what’s the issue with Gerber-Zavadskaya’s thesis?

MS: The conceptual problem lies more on the side of “rise“.

The very thesis that social sciences can only flourish under political freedom isn’t particularly well-supported by what we know of their history. Max Weber, Georg Simmel, and Sigmund Freud spent most of their lives and produced their most significant works under regimes of questionable democratic credentials. In the Soviet Union, scholars like Lotman and Kantorovich, Knorozov and Gurevich published articles and books that intrigued their foreign colleagues. Yet the 1990s—a period of unrestricted political and academic freedom, when collaboration with the West faced no constraints—witnessed the steepest decline.

If we take a discipline like sociology, we find that Russian scholars published two or three articles per year—some years, none at all. Then came a sharp increase. But this surge didn’t coincide with a period of greater freedom in Russia. Instead, it occurred around 2015–2017, when Western foundations had already been pushed out, the first research organizations were labeled “foreign agents,” Crimea had been annexed, and any whiff of freedom had long evaporated. Against this backdrop, social sciences suddenly experienced an unprecedented boom. In other words, this growth was not the product of unfettered collaboration with Western colleagues.

T-i: Then what did drive it?

MS: It was the result of state policies aimed at boosting international competitiveness. And here’s the irony: After two decades of academic freedom, cross-border collaborations, foreign funding, and minimal political pressure, the volume of English-language publications stagnated or even declined. The lowest point came in 2005–06, while growth began around 2009–10, peaking during the “Project 5-100” era, when HSE’s bonuses for foreign-language publications were adopted by other state universities. Naturally, this spawned a deluge of Scopus junk—but many institutions, anticipating further state demands, started incentivizing only publications in high-quality journals.

T-i: Couldn’t this simply represent a delayed effect, where earlier freedoms and international collaborations created the necessary conditions for growth, with results appearing later?

MS: That’s certainly possible. What gives me pause, however, is how conveniently this narrative serves as comfort to those of us who spent two decades organizing academic exchanges, internships, public lectures, and other educational initiatives. One could just as easily construct the opposite argument: precisely because the 1990s saw so much grant funding aimed at importing cutting-edge science into Russia, there was little incentive to publish in foreign languages at all. Most of those who saw themselves as emissaries of global science in what they viewed as a backwater of Soviet-style academia were only tangentially involved in actual research. Their role was largely limited to either importing ready-made Western scholarship or collecting raw data for foreign colleagues—while publishing almost nothing themselves.

Perhaps this period did leave behind a scattered layer of knowledge that the next generation eventually utilized. Books were translated and read; study abroad programs and research trips produced a cohort that moved beyond simply summarizing English-language articles for others and began writing their own.

But the immediate impetus for writing these articles stemmed from the Russian state’s anxiety about its global competitiveness. What did the Russian authorities want from universities? Rankings presence—more broadly, global soft power. Why did they want this? Because they perceived a constant threat emanating from the West and felt compelled to compete with it.

For the political regime, research universities have always served as an extension of this competition by other means. The Crimean Bridge and “Project 5-100” are not products of two different facets of the Russian regime – one rational, the other irrational. They stem from the very same impulse.

T-i: That’s an interesting and provocative thesis. But is this perceived external threat, this need to compete with and catch up to the West truly so central? Why not internal factors? I would argue, for instance, that the annexation of Crimea was primarily a response to internal rather than external threats.

MS: An externally-sourced threat perceived internally?

T-i: I’d contend that Russian authorities couldn’t have genuinely perceived any external threat at all, but rather chose to feign such perception for various important audiences.

MS: I won’t argue that point, but it’s somewhat irrelevant to our discussion of domestic politics. What matters isn’t whether the threat was real, imagined, or initially imagined yet made real through its consequences – like when Country A falsely assumes hostility from Country B, acts hostile first, and thus actually provokes hostility from B. It doesn’t even matter whether the ruling class genuinely shares these perceptions or cynically manipulates voters with them. What’s crucial is that under all these conditions, the regime will remain preoccupied with demonstrating its capacity to resist the external world.

This brings us to a critical yet often overlooked factor when predicting the Russian regime’s evolution, particularly in science policy. We might call this regime anti-Western. But Russia simultaneously harbors two competing varieties of anti-Westernism. Both view the West as hostile, treacherous, and intent on making our lives difficult. Yet one considers it inherently weak and flawed, while the other paradoxically sees it as a model to emulate. This creates an internal tension – we’re dealing with an entity we simultaneously admire, wish to resemble, and perceive as threatening.

The External and Internal West

T-i: This resembles the emergence of monotheism with its dualistic conception of a simultaneously benevolent and cruel deity.

MS: Psychoanalytic analogies about the Oedipus complex prove more tempting here. In Freud, the complex typically resolves through identification with the paternal figure as perceived by the son. Perhaps patriotic psychoanalysts (if such exist) might explain Russian Westernism thus: Westernizers create an internalized West they identify with, then proceed to hate Russia in its name.

Whatever the case may be regarding Westernism, Russia displays more prevalent reactions: most people never internalize the West, continuing to perceive it as external and hostile. They simply draw different conclusions – some dream of rapidly learning everything from it, others of isolating themselves from its influence to do things their own way. This isn’t uniquely Russian. Clifford Geertz in “The Interpretation of Cultures” contrasts what he calls “epochalist” and “essentialist” nationalisms. Essentialist variants advocate closing off from the world to cultivate uniqueness and divine election. Epochalist versions preach competing with the world by learning everything from it as quickly as possible – perhaps to eventually turn one’s back on it. In Russian political imagination, this position associates with Peter the Great.

T-i: Peter the Great and “turning one’s back”?

MS: To my knowledge, this “turning away” notion originates from Klyuchevsky’s remarkable (in multiple senses) lecture series “Western Influences in Post-Petrine Russia,” where he used it to illustrate Peter’s logic without claiming Peter actually said it. Yet it entered popular discourse as a direct Petrine quotation.

Both orientations can maintain highly confrontational stances toward the West – in fact, essentialism tends to be less confrontational than epochalism. To forget about the West requires believing it won’t invade us – possible either through confidence in military superiority (like 1840s Slavophiles) or by assuming the West doesn’t truly hate us. Conversely, epochalism pursues emergency, forced modernization (understood as Westernization) precisely because of intensely perceived threat.

Both factions stand opposed to the Westernizers—those who advocate for Russia’s full integration into the global economy, the adoption of Western-style electoral democracy, and unconditionally friendly relations with the West itself. This camp is willing to recognize the West’s political and moral leadership.

T-i: How does this distinction between epochalism and essentialism manifest in Russian social sciences?

MS: I wouldn’t claim this simple model explains everything in Russian politics, but it fits science and education policy remarkably well. Over the past decades, research policy has resembled a three-way Mexican standoff.

On one side are Westernizer-assimilationists who want Russian academia to mirror the West and fully integrate into global science. On the opposite end are classical essentialists who believe Western science is degenerate—its institutional models unfit for Russia, especially in social sciences. In extreme cases, these are mavericks crafting their own “theory of everything” and a unique academic system.

Then there are the epochalists—who, like assimilationists, seek to replicate Western institutions, but with a caveat: even if Russian science mimics the West, it can never truly join it, because Western science is part of a political system hostile to Russia. Their mantra? Learn fast, then surpass. Hence their obsession with global rankings and “competitiveness.”

T-i: Do epochalists suspect assimilationists of treason?

MS: They suspect even the essentialists of hating Western science simply because they are uncompetitive in it—leaving them no choice but to invent their own national tradition. Most Russian officials overseeing science policy fit, in this terminology, as staunch epochalists—and this did not start today. Count Uvarov, now being memorialized as an ideologue of reactionism, vigorously championed mandatory foreign research placements for young scholars earmarked for professorial chairs in Russian universities, as he had no faith whatsoever in the quality of education within the system under his control.

In this three-way Mexican standoff, the sides can form temporary alliances against one another. The science and education policy behind “Project 5-100″—and, more broadly, the “research turn” of 2011–2020—was a direct result of an assimilationist-epochalist coalition against the essentialists. Both groups favored international publications as the primary metric of scientific achievement. The former saw them as proof of their citizenship in real science, not some homespun imitation; the latter valued them as “soft power” in its purest form. Naturally, the essentialists from the first quartile writhed in protest, but their agony only reinforced the duelists’ conviction that they were on the right path. And, chronologically speaking, it appears the assimilationists succeeded in swaying the epochalists by convincing science bureaucrats that defenders of national traditions were little more than fraudulent, incompetent profiteers running dissertation mills.

T-i: How could the alliance between assimilationists and epochalists against essentialists have triggered the decline of Russian science?

MS: The alliance itself, I think, could not. The real issue is that the epochalists’ prophecy of an inevitable conflict with the West became a self-fulfilling one. Officials from the Ministry of Education and Science, of course, played no role in this. In their positions, they continued to pursue more or less the same epochalist line—as far as circumstances allowed. The “Priority-2030” program, which replaced “Project 5-100”, kept rewarding international publications until very recently. Meanwhile, those who tried to convince bureaucrats of the merits of indigenous science—like Dugin or former sociology dean Dobrenkov, who once championed the idea of “Orthodox sociology”—found no sympathy.

T-i: But couldn’t one counter by pointing to the establishment of the Ilyin School at RSUH (Russian State University for the Humanities)?

MS: Sure, but take a look at its webpage. The word “school” might conjure images of columns of students dutifully marching toward ideological indoctrination. In reality, this “school” is just another research center—one among dozens at RSUH, including centers for Holocaust studies and Sudanese research. It admits no students, and its founding statute makes no provision for such a thing.

It seems to me that among Alexander Dugin’s many diverse talents, none rivals his ability to convince liberal audiences that he holds sway over high-ranking officials (incidentally, his fellow patriots have always viewed him with far greater skepticism). Rare is the émigré media outlet that hasn’t reposted the news of his proposed reform of political science education. But Dugin has a long history of regularly proposing all sorts of schemes to eradicate Atlanticist influences—and what ever came of them?

The crux of Dugin’s predicament lies in the fact that those I’ve termed epochalists harbor an almost instinctive distrust of anything homegrown or idiosyncratic. When radical essentialists, speaking in the name of the Russian Orthodox Church, proposed purging the “alien” teachings of Darwin from school curricula, the Patriarch himself had to publicly apologize on camera. Even in seemingly more ideologically malleable fields like social sciences, the essentialists’ attempts to capitalize on the political climate—to forge their own “sovereign science” complete with blackjack and canonical thinkers—have led nowhere.

For years, Malofeev—a generous patron of all manner of indigenous intellectual ventures—has tried and failed to gain control over the Institute of Philosophy. Neither academicians nor bureaucrats have shown the slightest inclination to accommodate those peddling homebrewed philosophical alternatives. Under these conditions, any sweeping ideological reform of higher education—say, banning certain Western theories, or even all of them en masse, and replacing them with a Russian paradigm à la diamat—has inevitably faltered for one simple reason: the very decision-makers capable of enacting such changes inherently disbelieve in these alternative paradigms by definition.

The Irresponsibility of the Regime

T-i: Is it even possible to conduct social science research in modern Russia today?

MS: Generally speaking, yes—and not just abstract theoretical work, but empirical studies as well. We often imagine contemporary Russia evolving into something resembling the USSR. But in many ways, it’s the polar opposite of the Soviet Union—precisely in those aspects that matter for political control over social science research.

The architects of the Soviet regime were, first and foremost, intellectuals, and those who inherited their power wanted to appear as such. They took ideological foundations seriously. In the USSR, if someone took an interest in Wittgenstein’s philosophy, it was assumed they’d embarked on a slippery slope. After all, you couldn’t seriously engage with both Wittgenstein and Hegel. And those who rejected Hegel couldn’t properly appreciate Marx. And anyone who denied Marx was clearly anti-Soviet. This entire chain of reasoning—from grand premises to narrow conclusions—is utterly alien to modern Russia, despite the efforts of academic entrepreneurs like Dugin, who peddle their ideological “protection services” to the state.

There’s another key difference from the USSR. All political regimes are defined by what they take responsibility for. Classical Chinese political theory held that a dynasty’s legitimacy rested on the “Mandate of Heaven.” This mandate could be earned or lost—and its loss was signaled by droughts, floods, or other natural disasters. Here, the dynasty was accountable for literally everything.

Most regimes, however, have limits to their perceived responsibility. A government isn’t blamed for the start of a pandemic, but it is held accountable for imposing lockdowns. Yet if people ignore social distancing, that’s back to being not the regime’s fault. The Soviet system resembled ancient China in one crucial way: it claimed responsibility for absolutely everything. The regime asserted that society was being guided by a comprehensive, scientifically devised plan. Consequently, any mismatch between predictions and reality—any perceived problem—was framed as a flaw in the plan. Or at least in its execution—but since training personnel was also part of the plan, the blame ultimately circled back to the plan itself.

T-i: How did this affect Soviet science?

MS: Consider this example from the history of Soviet sociology. At one point, the Soviet regime decided that the “Soviet man” should embody the model of a devout Catholic in his family life—ideally, having only one sexual partner for his entire life.

No official statements were ever made, of course, regarding a single sexual partner. However, since premarital relations, extramarital affairs, and divorces were considered alien to socialist values, it followed that a second partner could only enter the lives of Party men and women in the event of widowhood. When the first sociological surveys were conducted (sometime in the 1960s), it turned out that the Soviet citizen was not always the model family man. By and large, Komsomol members—both male and female—did not differ much from their American peers. And this became a serious problem. First, it had been officially asserted that the bright future of the monogamous family under communism was a prediction made by the classics of Marxism-Leninism. Now, a troubling question arose: Had these classics been correctly interpreted? And were they even right to begin with?

In reality, Marx and Engels carefully avoided giving a definitive answer about the future of monogamy under communism. But admitting this would have raised further uncomfortable questions: What else had been falsely attributed to the classics? And who was to blame for misinterpreting their ideas in the first place? Ultimately, Soviet sociologists constantly struggled with the fact that even the most innocuous-seeming study could, in the eyes of the Party, morph into a large-scale ideological subversion—one that cast doubt on the legitimacy of the entire Leninist blueprint.

T-i: Because the regime was ideological?

MS: Absolutely. In this sense, the modern Russian regime is the polar opposite of the Soviet one. It hardly takes responsibility for anything. It’s like how various Russian governments have told voters since the 1990s: “You see, there’s inflation. Who knows where it came from—it just sort of happened on its own. Or take this crisis—it started in the West and then crept over to us; we had nothing to do with it. Corruption in the government? That’s like measles—no idea where we caught it.”

T-i: But don’t we see this same practice of shifting responsibility from the federal center to the regions—and to the governors?

MS: Yes. And let me emphasize: appointed governors. Somehow, the political center has managed to absolve itself of responsibility for virtually everything. At the level of legitimacy, Russia has already achieved the anarcho-capitalist ideal of a minimal state—one that answers only for the armed forces and its own self-perpetuation. That’s why election monitoring is unacceptable, and spreading “fakes” about the army is forbidden. But can you name a single case where anyone faced consequences for publicly criticizing the Central Bank or the Ministry of Education?

For such a regime, the findings of social sciences usually pose no threat. After all, what could they possibly uncover? Inequality and corruption? But the authorities themselves admit that Russia has inequality and corruption—a “painful legacy of the 1990s,” they say, or blame it on the people’s character. And it’s the same everywhere else, just read any sociology journal. Investigative journalism on corruption can be problematic because it names names. But sociological studies don’t identify individual corrupt officials—ostensibly to protect sources, though in practice, this protects the sociologists themselves.

Accordingly, cases where the authorities have reacted to the content of an academic journal article or, say, a dissertation, remain virtually nonexistent. In fact, the only remotely comparable incident involving direct intervention over a social sciences thesis predates the war entirely. It happened during the explosive growth in academic publishing—a period that, if we equate international publications with academic freedom, should have been one of total permissiveness. I’m referring to the case of Kirill Alexandrov and his dissertation on the Vlasovites. The objection wasn’t about Alexandrov personally—whether he attended protests or not—but about the dissertation itself. In the end, the Higher Attestation Commission denied him his doctoral degree. Yet the climax of this affair came in 2017, when “Project 5-100” was at its peak.

T-i: But surely there must be some areas that Russian social scientists would do well to avoid?

MS: In practice, there are a few rather narrow fields where the content of social science research could actually pose a risk to the researchers themselves. Aside from Russian elections, these include World War II and LGBT issues. And with the latter two, the reason likely isn’t that the regime perceives them as threats—but rather that it believes cracking down on them might score points with certain segments of the electorate.

No regime suppresses academic freedom just for the sake of suppressing academic freedom. There has to be either a perceived threat or a symbolic victory in it. Non-ideological regimes with diminished social accountability—like Russia’s—feel no danger from roughly 99% of what sociologists write, and even less from economists’ research (political scientists, admittedly, are worse off). Sure, you could score some points by clamping down on certain topics—but how many electoral points can you really gain by punishing critics of Russian education policy when even the public holds it in low regard? As a result, the state repression we do see is concentrated on direct political disobedience—if you’ve commented on current events in a university lecture, signed a petition, or donated to the wrong cause—rather than on the substance of dissertations or academic articles.

It’s not even clear why the repressive apparatus remains so indifferent to academic publications. Perhaps there’s some residual reverence for them. Or perhaps those carrying out these repressions simply don’t believe anyone actually reads these papers.

By designating universities as “undesirable organizations,” the Prosecutor General’s Office occasionally raised objections to the content of their academic programs, claiming, for instance, that students were being indoctrinated with “ultra-liberal models of democracy.” However, it never bothered to explain what exactly constitutes an “ultra-liberal model” or how it differs from regular liberal models (which, one assumes, remain permissible to teach). It’s hard to imagine that Bard College or Central European University (both now blacklisted) teach anything radically different from what’s offered in thousands of universities worldwide. If these particular institutions were singled out, the rationale likely lies not in their curricula but in their association with George Soros, their primary benefactor.

Russia now operates under a peculiar, barracks-style perversion of Humboldtian ideals—where no one cares what abstract theories you espouse, so long as you never openly refuse to follow orders.

T-i: Which, of course, doesn’t rule out censorship—especially self-censorship?

MS: If you ask around, you’ll hear no shortage of stories about censorship (or just read the ones compiled here). But interestingly enough, these are almost always stories about academic self-censorship. Just in the last few days, I’ve come across a few tearful letters from journal editors explaining to authors that they’d love to publish their articles—but, well, you know how it is. We’d run it, and then they’d shut us down, and after all the work we’ve put into this journal! You can find as many such stories as you like. But has even one academic journal actually been closed by the authorities?

Meanwhile, self-censorship is everywhere—and, at first glance, completely arbitrary. It seems that those who assume their loyalty is beyond question fear far less and allow themselves far more than those who believe the state remembers their liberal past and might be keeping an eye on them. So you get some demanding that cited authors be labeled “foreign agents” or “extremists,” others insisting they shouldn’t be cited at all, and still others who couldn’t care less—because, after all, they’re a journal of the Academy of Sciences, and surely that doesn’t apply to them.

T-i: But surely there must be some kind of policy regarding citations and terminology usage?

MS: So far, the Ministry of Justice and Roskomnadzor have shown no unhealthy interest in citations within academic journals—in fact, they’ve probably never even thought about them. This is why, in one “progressive” university, they’ll scrub any mention of gender from decade-old student papers, while elsewhere, courses on gender sociology are proudly advertised on official websites. And mind you, the latter might happen at an institution that’s spent the last decade building a reputation as one of the most reactionary (I won’t name names, but a quick search will reveal examples).

Meanwhile, at another university considered entirely “reliable,” a dissertation on Judith Butler’s philosophy was successfully defended in 2024—and not just on gender, but on full-fledged queer studies. Of course, to even grasp that, you’d need to read the word “intersectionality” without sounding it out syllable by syllable (again, no links provided).

Even more telling: in a recent war-attitude study by VCIOM—which likely assumed its well-known loyalty granted it leeway to state things plainly—it’s noted (verbatim on p. 216) that “convicted supporters of the war” in Russia amount to just 10%, significantly fewer than its staunch opponents.

What this reveals is that the suppression of academic freedom is largely self-inflicted, enforced sporadically yet vigorously by the very people being suppressed.

T-i: How has the thematic landscape of social sciences changed over the past three years then?

MS: Surprisingly little. This essentially confirms the prediction I made in my article two years ago—the one we began our conversation with: despite quantitative decline, Russian social sciences haven’t undergone substantial qualitative changes, even if operating at a reduced scale.

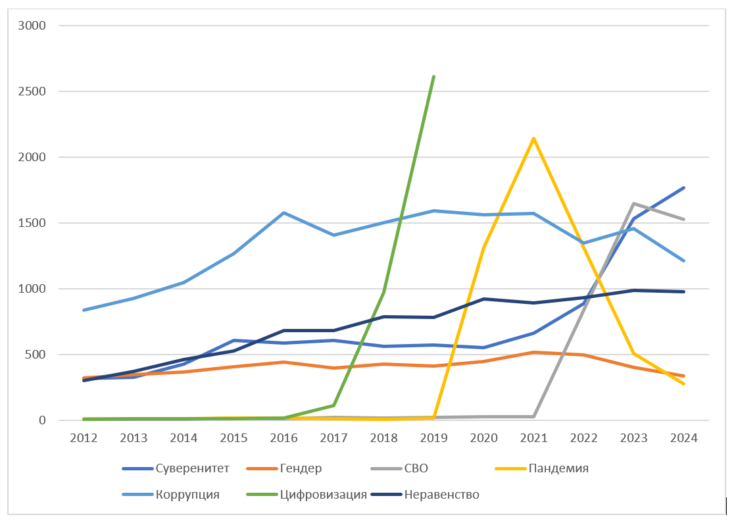

In recent years, I’ve attempted to track this empirically by analyzing keywords in titles and abstracts of publications indexed in the Russian Science Citation Index across three major social science disciplines: economics, sociology, and political science. Here’s what emerged.

The graph illustrates the trajectories of seven key terms. Four correspond to broad thematic categories: “gender” (which has become a symbol of the West’s perceived moral decline), “sovereignty” (the primary linguistic marker of contemporary Russian ideology), “inequality,” and “corruption” (research topics with clear critical potential). The remaining terms are tied to specific events or campaigns that academics felt compelled to address—”pandemic,” “SMO” (special military operation), and “digitalization.”

The data shows that “sovereignty” has experienced a meteoric rise, though not at the expense of other themes. Publications on gender and corruption have declined since 2021, yet these topics are far from disappearing. Conversely, the share of inequality as a subject of study, while growing slowly, continues to gain ground. However, all these trends are overshadowed by the explosive prominence of major themes like the pandemic and digitalization (I omitted extending the digitalization trendline on the graph, as by 2024, mentions had surged to 6,985, eclipsing even the ongoing war, the pandemic, and inequality combined).

That said, it’s worth noting that of the “hot-button” topics, the “SMO” proved the least popular. Although Russian social scientists strive to remain relevant and engage with pressing issues, many prefer to steer clear of this particular one—after all, who knows how things might unfold? Self-censorship can come into play from both sides.

The Judgment of History

T-i: How can we explain this phenomenon of self-censorship from a broader socio-historical perspective? Sometimes, conformists censor themselves as part of a historical process—when they have more to lose because their standard of living has risen.

MS: It’s unlikely that journal editors are worried about losing material well-being if they publish the “wrong” article—just as thesis advisors, when they warn grad students against risky topics, aren’t primarily concerned about their own livelihoods. In most cases, they’re probably thinking about the fate of their academic ventures or the well-being of those very students.

The real issue, however, is that there’s usually only one way to prevent the repressive machinery from doing its job: to do that job for it—albeit with less severe consequences for everyone involved, yet far more efficiently. The grim irony is that self-censorship tends to be much more effective than state censorship, because intellectuals themselves have a much clearer sense of which “wrong” conclusions a given theory or observation might lead to—especially if those theories have already led them there in the past. As a result, they may preemptively suppress ideas in which official censors would never even detect a dangerous subtext.

T-i: But didn’t the Russian university rectors who signed that ill-fated appeal go beyond mere self-censorship? Wasn’t their preemptive display of loyalty to the aggression a qualitatively different act?

MS: Top-tier academic administrators represent a whole new level of the same dilemma. On one hand, they hold some degree of power over who gets fired, who gets expelled, and which departments get shut down. Some will be dismissed with or without their cooperation (and along with them, should they resist)—but others, they might be able to shield, vouch for, or otherwise protect.

But this power lasts only as long as their own loyalty remains unquestioned. Now imagine a Western-leaning administrator who genuinely doesn’t want to dismiss like-minded colleagues (or even just anyone for political reasons). They’re being watched closely by two sets of eyes. One pair belongs to former friends and colleagues, now scrutinizing them for signs of loyalty to the regime—usually from a safe distance. The other belongs to the guardians of the status quo, meticulously searching for hints of disloyalty.

What earns points with one audience usually deducts them from the other. To afford losing even a few points with the authorities by sheltering dissenters, they must first accumulate those points through displays of extraordinary loyalty. And crucially, that loyalty must appear sincere—or at least mask unprincipled opportunism rather than overt opposition. There’s no winking at former colleagues and hoping the wrong people won’t notice.

T-i: This dynamic doesn’t seem particularly new for Russian academic administrators, does it?

M.S.: These patterns are actually best studied through the example of progressive Soviet institute directors who shielded ideologically “unorthodox” research—say, studies on the sex lives of Komsomol members. Now, those progressive directors could have spoken out against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, but they’d have instantly lost their positions, replaced by someone far less tolerant of ideological dissent. And that would’ve been the end of any safe space within their institutions.

So instead, they obediently held meetings, voiced full-throated support, and ordered the preparation of exhibits glorifying Soviet soldiers’ “international duty.” But there’s more. Many of these same figures—the most daring patrons of freethinking within their own institutes or departments—were simultaneously the most zealous crusaders against heresy elsewhere. As a result, those they protected and those who knew them in their other role retained utterly contradictory memories of them.

And then, the final layer of ambiguity: as long as these administrators remain in power, their protection of others is inseparable from the preservation of their own privileged positions. So their altruism will always be suspect.

T-i: How will future generations judge such people?

MS: Ultimately, it all comes down to who writes their history—and what kind of history it will be. Soviet directors were, in a sense, fortunate: their stories were largely told by those they shielded, who remained grateful. In all the Soviet sociological memoirs I’ve read, I can’t recall a single harsh word about academic leaders who failed to protest the invasions of Afghanistan or Czechoslovakia. For them, public words didn’t matter—everyone parroted the same lines. What did matter was whom they fired when those same colleagues were caught saying the opposite in the smoking room.

Today, though, we rarely hear from those protected by Russia’s current academic administrators—for obvious reasons. The voices that reach us usually belong to those who were purged. In some idealized future Russia, where all perspectives are heard, these narratives might converge. But we’re far from that.

There’s another crucial question: through what lens will future historians even care about today’s Russian academia? Progressive 19th-century editors—like those at “Sovremennik” (The Contemporary)—also had to explain to frustrated writers which ideas must never reach the censor’s eyes, just to salvage something publishable.

Yet we remember Nekrasov the editor not for the manuscripts he rejected, but for what he ultimately published. Most scholars who studied the history of “Sovremennik” came to it through their work on the history of great Russian literature. Similarly, how we’ll remember today’s editors—those rejecting “suspicious” articles—will largely depend on what they do publish in the end. If their journals’ names become associated with intellectual movements that changed the world, posterity will judge them far more kindly than if they’re remembered merely as case studies in political survival for survival’s sake.

T-i: Could something similar happen in modern Russia?

MS: Why not? Take sociology, for example. It’s clear that some of the most prominent research in the near future—perhaps the most prominent—will focus on integrating generative AI into research methodologies. And crucially, there appear to be no ideological barriers to working in this field. More broadly, contemporary Russia, much like the USSR before it, might end up fostering scientific careers as a form of escapism from an unpalatable reality—potentially attracting many talented young people to academia.

However, there’s another risk tied to an ostensibly inevitable (and even historically progressive) process that could have severe consequences for Russian scholars. Paradoxically, the first three years of the war saw no meaningful changes in science and higher education management. Minister Falkov announced the abandonment of Scopus and the Bologna System in the early weeks, but the former simply rebranded Scopus as the “White List,” while the latter seemed destined for a similar cosmetic overhaul.

The transition to a “national system” was postponed for years, with the only proposed change—ironically, the one element Russia had actually implemented—being the division into bachelor’s and master’s degrees. The expectation was that these would merely be relabeled as “basic” and “specialized” higher education, possibly extending “basic” programs from four to five or even six years. Universities would have welcomed this, since under the current per-capita funding model, longer study periods mean more teaching hours and, consequently, more faculty positions.

Yet, suddenly, in February of this year, the reform took a sharp turn—one that diverges radically from post-perestroika norms. First, the Ministry proposed restricting admission to “specialized education” (master’s programs) for graduates of unrelated “basic” degrees. Second, it reignited its campaign against “irrelevant” programs in state universities (e.g., technical institutes training lawyers) and private institutions, which—after a long hiatus—are once again seeing licenses revoked (the troubles at Shaninka might fit this context, irrespective of ideology).

T-i: But isn’t this essentially old news? We saw similar measures in 2014-17.

MS: Absolutely. What’s surprising is the timing. Given budget cuts, one would expect the state to let universities supplement their income through paid programs. Yet the Ministry is now talking about restricting paid admissions even at specialized state universities. Simultaneously, debates have revived about mandatory job placements for state-funded graduates, while Valentina Matviyenko controversially proposed limiting provincial students’ access to top metropolitan universities.

These developments reflect a broader ideological shift in higher education. Globally, only a few competing education philosophies exist. The technocratic approach asserts that universities should produce specialists tailored to national economic needs—with each graduate slot precisely matching labor market demands, ideally down to specific employers. This system thrives when universities merge with industries, much like the Soviet model during its most radical phases, when institutes were created at factories and universities were transferred to sectoral ministries.

The liberal philosophy, by contrast, views education as serving personal growth, with society benefiting from accumulated human capital. Since future labor needs are unpredictable—who knows if a given job will even exist by graduation?—it makes little sense to train specialists for specific roles from adolescence. Moreover, forcing 17-year-olds to choose a lifelong career path—especially when retraining is costly and difficult—is like having teenagers select a life partner straight out of school. Some might get lucky, but overall, it’s a flawed concept.

Russia as Harry Potter

T-i: Are there other ideologies of higher education worth mentioning?

MS: Certainly. Take the social engineering approach, which views university admissions as a tool for promoting social mobility, nation-building, or similar goals. Most higher education systems balance these ideologies to some degree. The Soviet model was predominantly technocratic, with situational social engineering—favoring applicants of proletarian origin, ethnic quotas (both positive and negative), and so on. The post-Soviet period, by contrast, saw concessions to liberal ideals. Social engineering resurfaced in the form of the Unified State Exam (EGE), which boosted opportunities for provincial students, thereby unifying national space—though at the cost of regional depopulation.

Now, we’re witnessing a return to technocracy and regional reinforcement—but this comes at the expense of geographic mobility, a risky move given how regional inequality will now be perceived by local populations.

Simultaneously—and this is crucial for the future of Russian social sciences—this same revolutionary February saw the Ministry announce a reboot of “Priority-2030”, the successor to “Project 5-100”. Originally, “Priority-2030” aimed to correct “5-100″’s key flaw: imposing a single, unattainable development model (a “world-class research university”) on institutions for which it was utterly unrealistic.

T-i: It seems that even at the launch of “Project 5-100”, its characteristic liberal utopianism was quite obvious to many. Today, this utopian quality may be perceived as definitively self-evident – sometimes even with a tinge of nostalgia.

MS: Expecting faculty at an average university to benchmark themselves against Cambridge is like demanding they become fashion icons on their salaries, keeping up with the latest trends.

Being a style icon is a full-time job – one requiring not just appropriate compensation but an entire support staff. It’s hardly the professors’ fault that when trying to meet these new demands, the best they can manage is a “Gucci” bag from the local flea market. Let me add in passing: this is by no means a uniquely Russian problem. Higher education worldwide suffers from the lack of a positive image of the solid middle-of-the-road institution – universities that do their job well without reaching for the stars.

Thus, the original version of “Priority-2030” acknowledged this problem and established three categories: research universities expected to meet standards similar to “Project 5-100”; regional growth drivers focused on industry collaboration rather than publications; and numerous institutions receiving smaller 100-million-ruble grants primarily for educational tasks.

T-i: Are you suggesting that “Priority-2030” has abandoned the distinction between research and technology tracks, effectively eliminating the research-focused path?

MS: Precisely. The new “Priority-2030” criteria omit publications and Scopus quartiles entirely. Minister Falkov framed it bluntly: “We’ve competed in one sport—now enough.” The new “sport” for universities is collaborating with companies to produce high-tech goods. His February 8th address on Russian Science Day made these priorities unambiguous. While some might have expected mentions of Lobachevsky, Mendeleev, or Pavlov, the minister named Korolev, Tupolev, and Zhukovsky instead. Technological leadership—now “Priority-2030″’s official goal—has clearly superseded research leadership, which is quietly being phased out.

T-i: So what’s the status of academic publications now?

M.S.: It’s not that publications have vanished entirely from reporting requirements. They still matter for institutes under the Academy of Sciences, the Russian Science Foundation (RSF), and dissertation defenses. In fact, the official 2035 roadmap for Russia’s scientific and technological development even lists “number of publications in high-impact journals” as a target—one that’s technically projected to grow. Though that growth is just 10% over a decade (from 140,000 to 155,000), which, given bureaucratic tendencies to inflate targets, suggests the government would be pleasantly surprised if output merely doesn’t decline.

Here’s the crux, though: universities were the primary vehicle for realizing the state’s scientific ambitions. Now that they’re no longer held to these standards, no one is concretely accountable for this part of the plan. Tellingly, as colleagues recently noted, the RSF’s three-year development program explicitly plans to reduce both grants issued and resulting publications.

T-i: Does this signal Russia scaling back its global scientific ambitions?

MS: Collectively, this suggests Russian authorities have reached the “acceptance phase,” resigning themselves to the inevitable. Throughout the 20th century, the Russian Empire and later the USSR ranked among the top five scientific powers. After the USSR’s collapse, the brain drain of the 1990s, and chronic underfunding, Russia slipped to around 10th place—comparable to the Netherlands or Australia. With the new wave of emigration and shifting state priorities, it will likely fall further, perhaps to 20th, closer to Denmark. But competing with Denmark holds little appeal for national pride or soft power, so authorities have essentially waved the white flag in this arena. Russia’s history as a scientific superpower now appears officially concluded.

T-i: You seem to view this loss of national ambition as somewhat progressive. Could you explain the paradox?

MS: There’s a risk of wishful thinking here, but acknowledging the inevitable carries a glimmer of realism—something Russian science policy (and policy in general) has always lacked.

When the Russian government anticipated doubling publication output within a decade, it operated on a naive faith in the boundless ingenuity of Russian scientists—that with just the right mix of carrots and sticks, they’d make breakthroughs to shake the world. Now, it seems miracles are no longer expected of them.

Interestingly, just a couple of months ago the new goals of science policy were framed as “technological sovereignty” – today the word “sovereignty” has disappeared, replaced by the more vague and thus more plausible “leadership”. After all, it’s unlikely any single country can boast complete sovereignty, whereas dozens can claim leadership in at least something.

T-i: Does this connect to what we discussed earlier—the central divide in Russian politics between those who see the West as eternally, implacably hostile toward Russia, and those who don’t?

MS: Absolutely. My personal, entirely speculative theory is that Russia is a victim of the Mercator projection. When we look at a world map, we see a vast blot covering a third of the landmass, making all other countries appear like dwarfs in comparison. Naturally, it should have the most resources. And it has human resources, equally boundless. Russian soldiers are the hardiest and bravest. Russian scientists may be lazy and prone to cutting corners, but they’re the most talented in the world. Therefore, other nations—especially those vying for hegemony—cannot help but fear Russia and seek to subjugate, conquer, and carve it up.

Russia is like Harry Potter. As long as it exists, no Dark Lord can rest easy. A clash between them is inevitable—hence the perpetual sense of threat. But looking at things realistically, it turns out they can rest easy. Those resources can probably just be bought from you anyway, and the dusty cabinets of Soviet design bureaus don’t hold blueprints for a perpetual motion machine. So it turns out the would-be hegemons might not care much about Russia after all. And you can, in principle, live a quiet life, minding your own business without constantly preparing for a mortal showdown.

Acknowledging that you don’t occupy a unique place in the world is a rather sad thing, both personally and collectively. On the other hand, it’s the only way to rid yourself of both the obsessive idea that everyone secretly envies and therefore hates you, and the irrational hope that with just a little more effort, you’ll break through to unimaginable heights. The current shift in science policy seems to hint at some subterranean maturation. Here’s hoping it doesn’t stop there.