As the bill granting the FSB control over scientists’ international cooperation advances through the Duma, universities have begun tightening scrutiny of all academic materials and public statements—under the guise of “state secret” checks. Though interagency guidelines on state secrecy were issued to universities over a decade ago, the era of total control is just beginning. Staff at Moscow State University (MSU) shared with T-invariant a new directive threatening to revoke bonuses and stipends for non-compliance. Similar orders have emerged at other institutions.

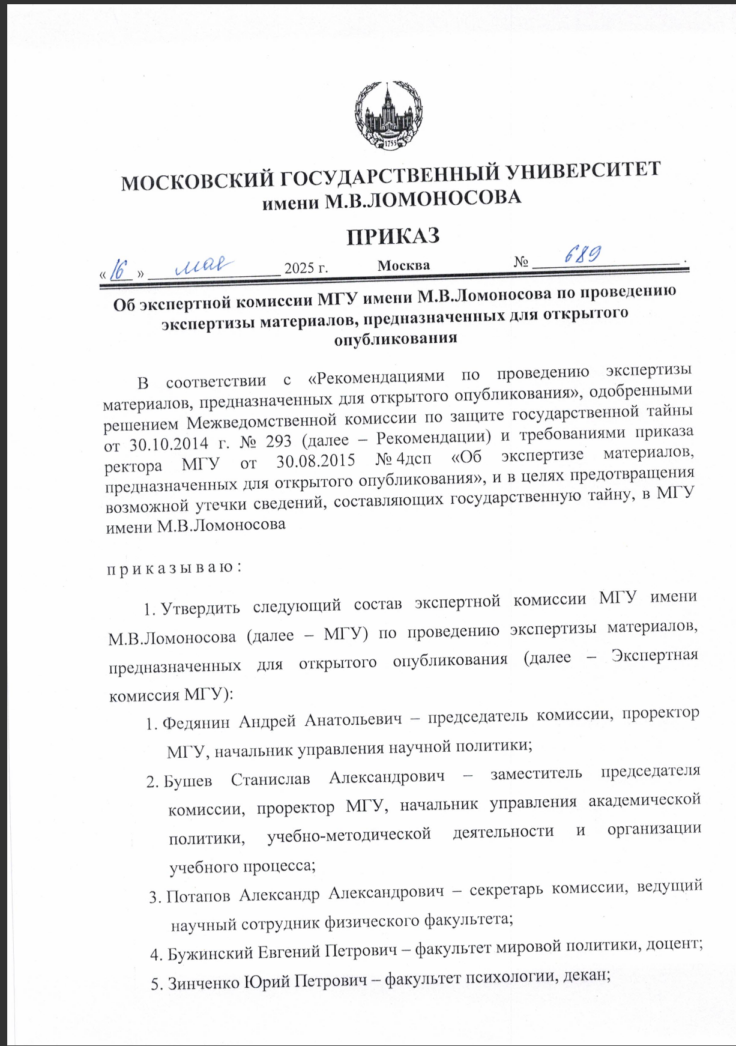

A new decree issued by MSU on May 16, titled “On the MSU Expert Commission for Reviewing Materials Intended for Public Dissemination” (obtained by T-invariant), introduces stricter regulations on the evaluation of any public academic output. According to the order, faculty members must now submit not only articles and monographs for review but also any other materials, including conference abstracts and presentations. The stated objective of the policy is to ensure that no classified state secrets are disclosed in such texts. However, the wording of the decree is broad enough to allow for an expansive interpretation of which materials fall under scrutiny.

State Secrets

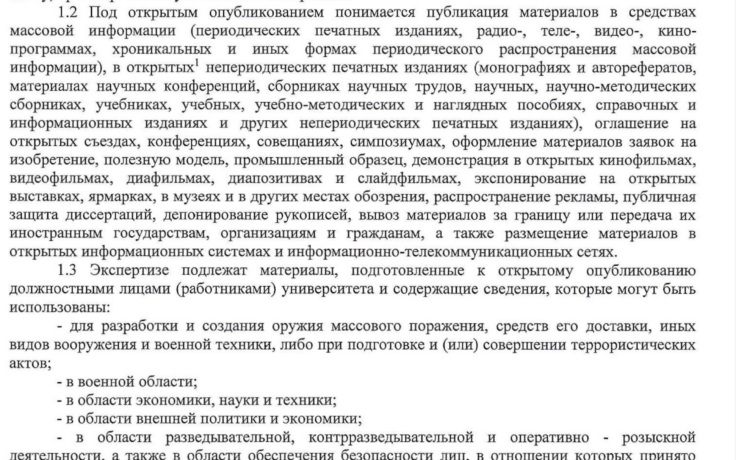

For years, certain information pertaining to military affairs, intelligence, and related scientific-technical data—classified under Article 5 of the Russian Federal Law No. 5485-1 “On State Secrets” (21.07.1993)—had to be submitted to special expert commissions for clearance before being published openly.

The current MSU decree cites guidelines from the Interdepartmental Commission for the Protection of State Secrets (30.10.2014) and a similar 2015 order by the university’s rector. It was then that the boundaries of what could be deemed a “state secret” began to blur and expand. A decade ago, MSU faculty reacted far more vocally to a comparable policy change. For instance, scientists contacted Nature to report that their submissions now required “pre-moderation” by the FSB before being sent to academic journals or conferences. In response, MSU administrators and officials from the Ministry of Education and Science insisted there was no cause for concern. At the time, the new rules were linked to broader amendments to state secrecy laws, enacted during the first phase of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Commenting on the developments, Yuri Ryzhov, a Russian Academy of Sciences academician and human rights advocate, remarked: “Every university has—and always will have—a security office or a “First Department” overseeing classified matters. But even in Soviet times, they never vetted academic papers.”

Ten years on, MSU employees appear unwilling to openly challenge the administration’s latest order. However, several faculty members who spoke to T-invariant on condition of anonymity say the current situation differs drastically from past practice. The new system of vetting academic and educational materials has been implemented gradually—for instance, as early as 2022, the rector’s office circulated detailed guidelines on the updated rules.

“Back then, these directives existed, but no one took them seriously, much less enforced them. Most staff weren’t even aware of the decisions or simply ignored them. Now, they’re being reminded. The administration has adopted a much tougher stance this time, which is why I’m more concerned than before. They’re quoting the order verbatim: “Submit all materials for review.” There are threats of losing bonuses and stipends,” an MSU professor in the social sciences and humanities told T-invariant.

The outlet has confirmed the tightening of review requirements with faculty members from political science, philology, and biology departments.

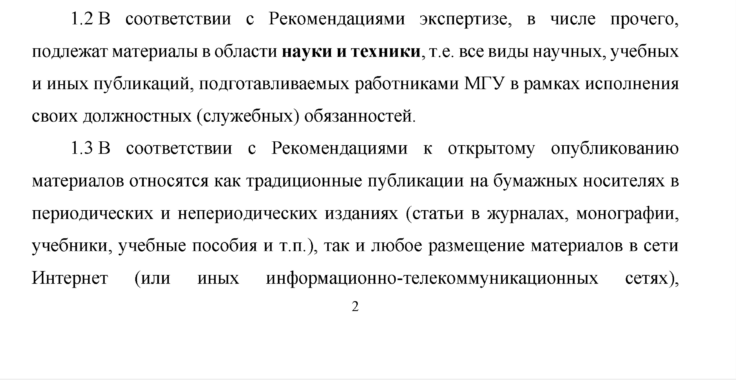

The official guidelines specify the scope of controlled materials as follows: “All MSU employees must prevent the open publication of any materials produced as part of their official duties until receiving formal approval—including a properly issued expert review confirming the content is cleared for public release.”

The term “open publication” also encompasses oral presentations at dissertation defenses, seminars, conferences, and exhibitions; media publications; and the submission of any materials (including peer reviews) to academic journals or edited volumes—even if the text was ultimately rejected or remained unpublished.

The new restrictions at MSU fit squarely into the wider patterns observed in 2025. As previously reported by T-invariant, the FSB has been tightening oversight of scientists’ international contacts through a comprehensive draft law, which has already cleared its first reading in the State Duma.

“The university’s directive under discussion strikes me more as bureaucratic folly than systemic pressure from security agencies. Whether out of fear, shortsightedness, or a desire to curry favor, MSU has gone beyond even the most formal recommendations of the Interdepartmental Commission on State Secrets Protection,” a T-invariant source commented.

According to the order, MSU’s Expert Commission comprises 37 members. Alongside Andrey Fedyanin, the vice rector overseeing the entire document (who heads the Science Policy Department), and Stanislav Bushev, vice rector for Academic Policy, the list includes a diverse range of individuals. Some faculties and institutes delegated deans or their deputies, while others sent associate professors or research fellows. The logic behind the selection is unclear: while certain faculties have 2-3 representatives, some natural science departments are represented by just one junior staff member.

Questions have also arisen regarding the stipulation that “the submission and collection of materials sent for review by MSU’s Expert Commission will be handled in Room 663 of the MSU Fundamental Library.” Does this mean that all research and teaching staff across the university’s departments—roughly ten thousand people—must submit physical copies to a single office? This remains unclear. The T-invariant editorial team has sent a request to the university’s press service and is awaiting a response.

If materials are written in a foreign language, they must be translated into Russian, including all possible “elements of the original content—illustrations, tables, formulas, etc.” The document’s authors separately emphasize adherence to the norms of “modern literary Russian.” Yet bureaucratic humanism also makes an appearance: if “materials in the humanities” (e.g., philology, linguistics) contain “foreign-language content elements,” translation may be waived.

Separately, certain large structural units of MSU are establishing their own expert commissions to evaluate submissions from smaller departments.

This formal adherence to the Interdepartmental Commission for State Secrets Protection guidelines is not unique to MSU. For instance, Ural Federal University’s (UrFU) website publishes similar review templates, regulatory documents, and guidelines resembling MSU’s framework. There, “open publication” encompasses virtually any form of written or oral communication: from research articles to public speeches, teaching seminars, and media publications. The topic is irrelevant—beyond military affairs, weapon development, or intelligence matters, restrictions also apply to “economics, science, and technology” as well as “foreign policy and economics.”

“In other words, the spectrum ranges from weapons of mass destruction to Pushkin studies,” a prominent physicist remarked to T-invariant.

The First Departments Have Risen in Status

The task of overseeing the comprehensive expert review will now fall to specially trained personnel from the first departments—units that have once again become a prominent feature of university and institute life. The existence of first departments, “seconded personnel,” and individuals with various other titles was first brought back into public discussion during the early years of Vladimir Putin’s presidency. As far back as 2005, students approached Yaroslav Kuzminov, then rector of the Higher School of Economics (HSE), to ask whether it was true that an FSB officer had begun working at the university (Novaya Gazeta reported on this at the time, and HSE even published the article on its website—uncensored and still available today, reading like a document from a different era).

The involvement of the FSB in universities varies across institutions. In some, like the HSE and the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT), high-ranking officials with security backgrounds hold vice-rector positions—their biographies openly listing extensive FSB experience. For instance, Sergey Rozhkov, before joining HSE, headed the Belgorod regional FSB and served as deputy chief of the FSB directorate in Tatarstan. Meanwhile, Vladimir Petushkov, MIPT’s Director of Security and Regime, chose not to elaborate on his background but still acknowledged his FSB affiliation. A vice-rector position has become a common career path for former regional FSB chiefs—some keep a low profile, while others, like those in Krasnoyarsk, frequently appear in the news.

However, not all security officials in universities come from the FSB. At MIPT, for example, the Director of Security is a former Interior Ministry (MVD) officer. Similarly, Togliatti State University has a vice-rector with an MVD background. Another source of university security personnel is the MVD’s Center “E” (Extremism Prevention Centers), staffed by operatives primarily tasked with monitoring opposition figures, peaceful protesters, and conducting “preventative” home visits.

A striking example is the administration of St. Petersburg State University (SPbGU): Acting Vice-Rector for Security Dmitry Gryaznov and his deputy for “general affairs,” Oleg Shaydulin, previously led the political department of St. Petersburg’s Center “E.” Shaydulin gained notoriety among locals for personally visiting activists’ homes to issue administrative offense reports before his university appointment—a fact widely covered by local media.

Some institutions, like ITMO University and Siberian Federal University, do not list FSB-linked officials on their websites but maintain “First Departments”—a Soviet-era term for security oversight units. Ural Federal University goes further, publishing the First Department’s contact details alongside downloadable forms for state secrecy clearance and even travel permits for leaving Russia.

MSU, however, shows no obvious traces of security personnel on its website—though sources interviewed by T-invariant confirm their heavy presence. This became particularly evident during the 2018 FIFA World Cup, when student activists protested against a massive fan zone near MSU’s main building and clashed with security officials. The incident was detailed in an open letter, highlighting the FSB’s entrenched role in the university.

Back in the early 2000s, a nondescript office near the reception of Viktor Sadovnichy, MSU’s long-standing rector, housed Stanislav Puchkov, the university’s security aide. Located on the 9th floor of the main building, Puchkov’s presence left a lasting impression on faculty and staff. In 2008, Puchkov became embroiled in a high-profile scandal involving the assault of Mikhail Sukhodolsky, the son of a deputy interior minister, at an MSU café. Sukhodolsky, then an economics student, was reportedly beaten in an altercation that led to rumors of Puchkov’s dismissal and even a clash between two security agencies. Yet records indicate Puchkov remained at MSU as late as 2013, still authorizing key security documents.

Currently, MSU’s First Department is headed by an individual named A.N. Lyulko – his signature appears on recent official documents (the MSU research portal “ISTINA” lists a profile matching these initials, though the editorial team has not yet been able to independently verify this correspondence).”

Back in the USSR

Many MSU researchers who spoke with T-invariant say they haven’t yet faced mandatory review demands for their publications or speeches—but few doubt the tightening trend.

“The new order hasn’t been formally announced, but it’s not the first time we’ve heard that a paper submitted for bonuses could be rejected over a missing expert review certificate,” said a physics faculty member.

A recently resigned researcher from one of MSU’s science departments was blunter: “I’ve seen this “expertise revival” crap before. Nothing new—it’s pure Soviet déjà vu. Back then, every journal submission needed a certificate proving it contained no state secrets. That system lasted until the USSR collapsed. Then, by late 2022, MSU tried to revive it half-heartedly. Some paperwork carousel spun briefly before everyone gave up. Now, it seems they’re serious about bringing the Soviet model back for good.”

Many interviewed scientists fear the emerging review system could out-Soviet the Soviets. They interpret MSU’s order—and the administration’s heightened scrutiny—as signs of a new era. Under the USSR, ideological control followed clear, predictable rules. Today, the haphazard demands of university officials and security agencies leave researchers in perpetual uncertainty—never knowing what might trigger repercussions.

MSU’s order (like the proposed FSB oversight of international research contracts) presumes scientists guilty until proven innocent: guilt is now determined through exhaustive reviews, requiring certificates attesting that any written or oral statement contains no state secrets, “ideological subversion,” or even vague “discreditation.” And the mention of Room 663 hints at the Kafkaesque bureaucratic absurdity awaiting those who dare publish without permission.